Leadline 1994: Colour and Light: Image and Emanation (Part Five)

by Jason Peter Brown on July 29, 2007

by Jason Peter Brown on July 29, 2007

Filed Under: REPRINTINGS, LEADLINE, STAINED GLASS, ART

Filed Under: REPRINTINGS, LEADLINE, STAINED GLASS, ART

This editorial was written by Doreen Balabanoff, and originally appeared in Leadline in 1994. Part five of six. You can read Part One here.

In 1857 Ruskin suggested to the Architectural Association the construction of "one blazing dome of many colours" over all of London… "that shall light the clouds round it with its flashing as far as the sea". By 1914 Paul Scheerbart, Berlin bohemian poet and novelist, had expanded this notion to a full fledged treatise on a world set right by coloured glass. In his book Glasarchitektur, he wrote:

"If we want our culture to rise to a higher level, we are obliged for better or for worse, to change our architecture. And this only becomes possible if we take away the closed character from the rooms in which we live. We can only do that by introducing glass architecture, which lets in the light of the sun, the moon, and the stars… through every possible wall, which will be made entirely of glass - of coloured glass. The new environment, which we thus create, must bring us a new culture." Sheerbart dedicated the book to his friend, architect Bruno Taut, who was simultaneously opening a 'Glass House' pavilion at the German Werkbund Exhibition. The pavilion, sponsored by the German glass industries, "crystallized the Scheerbartian concept of an architecture of glass and concrete."

Dennis Sharp, in his introductory remark to the English edition, goes on to describe the pavilion:

"Glass was everywhere; walls, ceilings, floors and even staircases were all finished in some kind of translucent or transparent material. Taut's aim was 'the enclosure by means of glass' and he playfully introduced coloured glass, opaque glass and clear glass to create various effects of distance, silhouette and nearness… Glass in 1914 was being tested by Taut as a vehicle for expression rather than as an adjunct to the philosophy of a 'new' or 'modern' architecture of the type envisaged in Germany after 1924."

Taut formed a group of "paper visionaries" called the Glass Chain, who corresponded with one another for several years, exploring the use of coloured glass as a primary architectural strategy.

Elsewhere, individual architects like Perret, Kazis, Corbusier in France, Steiner in Switzerland, and Wright in the U.S. experimented with similar ideas in actual built projects. Frank Lloyd Wright, presumably without knowledge of Sheerbart and Taut (as yet not translated into English in 1928), wrote:

"Imagine a city iridescent by day, luminous by night, imperishable! Buildings, shimmering fabrics, woven of rich glass; glass all clear or part opaque and part clear, patterned in colour or stamped to harmonize with the metal tracery that is to hold all together…"

But the reality of glass architecture, probably largely for practical and economic reasons, was not to be a coloured new world. The functionalist machine aesthetic, coupled with the manufacture of float glass in large dimension, eventually took hold. Sheerbart's conceptual world of coloured glass, considered today by some historians as instrumental in the development of glass architecture itself, came to be seen as a whimsical fantasy. Thus disconnected from the conceptual design arena, coloured glass became, in the eyes of modern architects, something nostalgic, historical, technically and financially difficult.

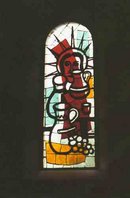

As if to defy this dismissal, modern European painters took up the medium and explored it, often in retrofitted projects. Evie Hone in Ireland, John Piper in England, Matisse, Chagall, Manessier, Roualt, Cocteau, Braque and Leger in France were all contributors to a renewed understanding of the medium. These artists dispensed with the stultifying rigours of "traditional" glass painting, with its studied application of layer upon layer of 'properly executed' painting fired onto the glass (in a misguided effort to replicate the translucent softness of timeworn medieval glass). The idea of stained glass as a medium of architectural interplay with colour and light was reborn in their work.