Leadline 1994: Colour and Light: Image and Emanation (Part Two)

by Jason Peter Brown on July 21, 2007

by Jason Peter Brown on July 21, 2007

Filed Under: REPRINTINGS, LEADLINE, STAINED GLASS, ART

Filed Under: REPRINTINGS, LEADLINE, STAINED GLASS, ART

This editorial was written by Doreen Balabanoff, and originally appeared in Leadline in 1994. Part two of six. You can read Part One here.

By 1980, the American glass artist Jamie Carpenter was noticing a de-emphasis on the "the physical phenomenon of light transmittance" in this work. Lecturing at the New York Experimental Glass Workshop, he told a conference of glass artists:

"My only concern in relation to this type of work is that it inherits the assumption of the window as an essentially graphic image. The window does function with the architecture in a linear sense, but this linearity is only a modified form of graphic signage… this function can easily be answered by any number of materials."

Carpenter's own interpretation of stained glass as cinematic projection, outlined in his N.Y.E.G.W. address and later published in New Work magazine, was a reminder of some of the most potent possibilities the medium has to offer. But his was a lonely voice in the stained glass world of the 70's and 80's.

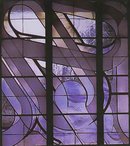

Yet Carpenter's harsh judgement of the German work was not entirely justified. Certainly the 'graphic' sensibility did not entirely overwhelm issues of light and colour. Schaffrath's windows at St. Johann, Merkstein (1974), for example, do use light transmittance marvelously. Many German works of the period do use colour effectively, even provocatively.

Then again, German artists who chose a less "architectural" approach simply were not seen or heard of in North America. For example, the painterly work of Hans Gottfried von Stockhausen and his colleagues and students, known as the "Stuttgart School" (after the influential years he spent teaching at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenen Knste Stuttgart from 1970 to 1985), is only recently receiving some North American exposure.

But through the increasing use of opak glasses, many of the German artists did produce works which (sometimes consciously), evoked the kind of illuminated image we are familiar with in billboards and television screens (a point of arrival not without an element of irony, considering the commercial colour exploitation Schaffrath had set out to avoid.) But "light through", as Montreal artist (and linguist) Eric Wesselow has called it, "that light which penetrates and therefore illuminates", was well known to us in the natural world long before we met it in illuminated commercialism. We've known it in the sunlit glow of a leaf or flower petal… we've seen it in the shafting blue-green haze of an underwater experience. And once it reigned supreme in the "unnatural" world… in the medium of stained glass.

"I think of Robert Sowers (The Lost Art)", writes Ted Goodden, "pointing out the obvious with his light meter - comparing the lumens reading of watercolour painting with stained glass. The jump from reflected to incident light is a quantum leap… Colour on the wall is not at all the same thing as colour in your face… in music the comparison would be between a harmonica and the organ installed at Notre Dame. Stained glass artists should probably be licensed like electricians. They manipulate the same voltages."